[PERLAK] Fikzioa II: Laxalten bertso-western bat (1963)

Laxalten bertso-western bat –

Robert Laxalt jada aurkeztu dugu National Geographicen bertsolaritzari aipamena egiten zion testuaren egile gisa. Ez da hori, ordea, bertsolaritzaz argiratu zuen testu bakarra. Bere fikziozko lanetan ere jorratu zuen gaia. Ekarpen hori aztertu duen David Ríok honela dio, esaterako:

Laxalt es plenamente consciente de la gran relevancia del factor oral en las tradiciones vascas. De ahí que en ‘In a Hundred Graves’ los elementos de carácter vocal ocupen un lugar de privilegio, imponiendo su dominio sobre la palabra impresa. En concreto la obra da fe de la importancia de las voces de los bertsolaris (trovadores) frente al escaso prestigio de los poetas en esta sociedad (Río, 2002:88)[1].

Prentsan argitaraturiko fikzioan ere egingo dio tarte bat bertsolaritzari Laxaltek. Honela, 1963ko urrian hasi eta buka gaiari eskaintzen zaion harribitxia aterako da The Atlantic Montly aldizkari estatubatuarrean: The Basque troubadour.

Kultur eta literatur aldizkari bat da The Atlantic Montly, 1857an Bostonen sortua eta egun egoitza Washingtonen duena, garaian garaiko idazle estatubatuar entzutetsuenen lan motzen argitaratzaile eta hamarkada askoan salmentetan nahiz oihartzunean New Yorker handiari Estatu Batuetan itzala egin izan dion bakarra. Laxaltek bere lana argitaratu zuen garaian ere prestigio handiko argitalpena zen, eta suposa daiteke zabalkunde polita izango zuela. Izatez, Laxalten testuaren literatur kritika bat ere topatu ahal izan da 1963ko azaroaren 11n Reno Gazetteegunkariaren 8. orrialdean argitaratua.

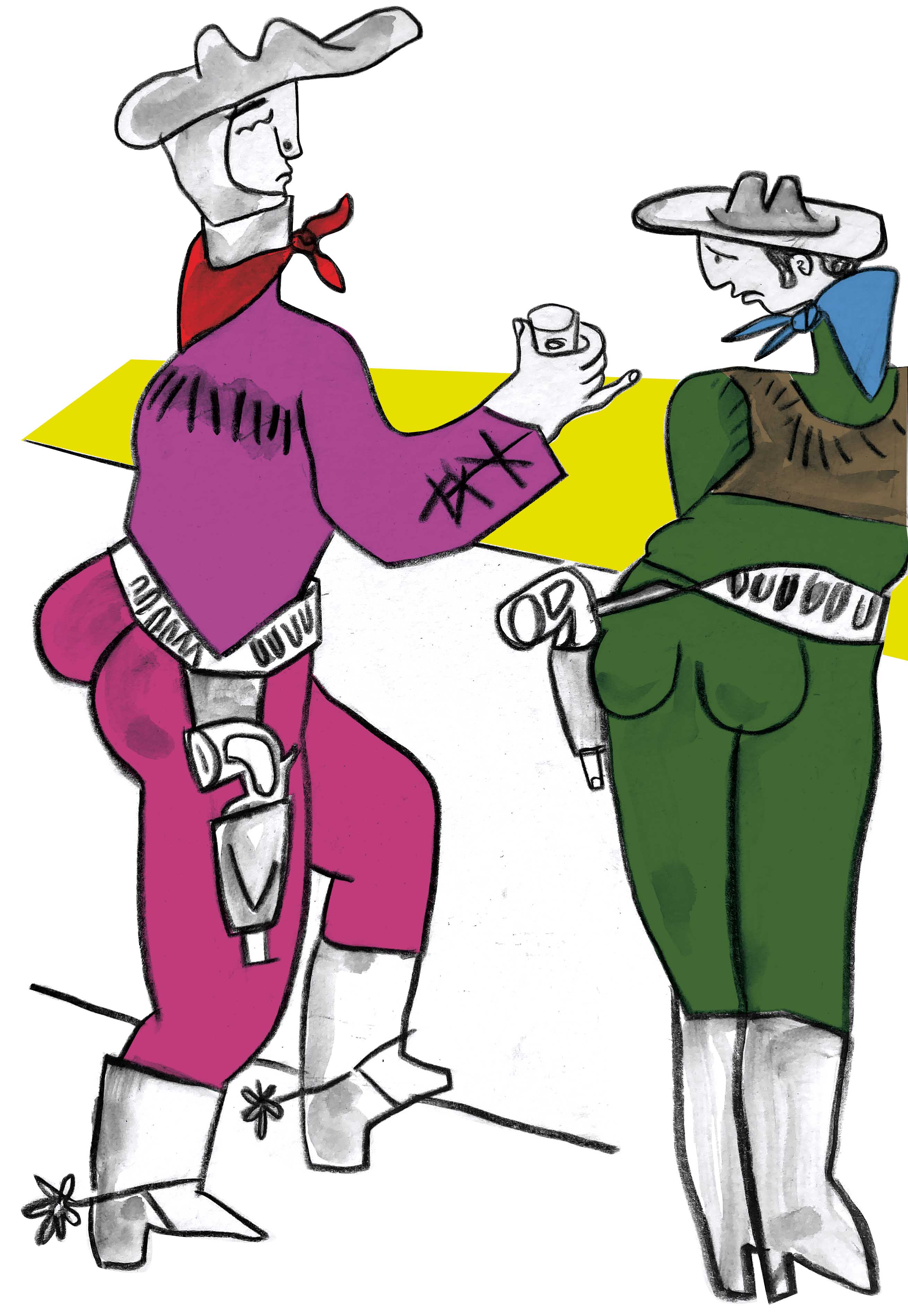

Aldizkariaren hiru orrialde hartzen ditu lanak, eta hainbat ilustraziok janzten dute.

EUSKAL TROBALARIAK

Pleasures and places darama azpititulutzat testuak eta bere lehengusuarekin Pirinioetan buelta bat eman ondoren bustita eta hozturik herrixka bateko tabernan aterpea bilatzen duen narratzaile amerikarraren ahotsa eskaintzen digu.

Ilustrazio nagusiak, ezpatazko duelu batekin alderatzen du bi bertsolariren arteko lehia, baina testua irakurrita, eta idazlea euskal jatorriko iparramerikarra dela jakinik, western bateko bi pistoladunen artekoaren traza hartu diogu gehiago.

Horra, esaterako, lehen bertsolari pistoladunak, gauaren erdian, tabernan egiten duen sarrera:

“Tabernako atea ireki zen eta irudi bat agertu zen ilunpetik; bere aterkiko ura astinduz sartu zen. Zalantzarik gabe artzainarena zen janzkera zeraman: txapel zabala, galtzerdiak bere bernatan estu-estu bilduta eta euritarako kapa urdin eta luze bat. Bere aurpegia antzinako euskaldunena zen, luzea eta zorrotza eta bere itxuran harrotasuna nabari zen, ia harrokeria. Besteen agurrei eskuarekin agur eginez erantzun zuen eta bere begi beltzekin taberna osoa gainbegiratu zuen”.

Edo bi bertsolari pistoladunak begiradak gurutzatu eta bakoitza tabernaren punta banatan jartzen direnekoa: “Gure atzean zutik zegoen nekazaria ikusi zuenean, geratu egin zen. Buruarekin agurtu zuen, errespetuz, bere aterkiaren kirtena kapako lokarrian lotu zuen eta tabernaren beste puntaraino joan zen oinez”.

Begiradarekin desafioa onartu duen bertsolariaren deskribapena ere ez dabil urrun westernetako saloon batean borrokarako gertu dagoen pistoladunaren iruditik: “Gure ondoan zutik zegoen nekazariari begiratu nion. Barraren gainean zegoen makurtua, itxaroten. Bere begiak erdi ezkutuan zituen aurpegi betean, eta bere ezpainetan irribarre maltzur bat marraztu zen”.

Bera izango da ‘tiro’ egiten lehena:

“Nire bizkarra zeharkatu zuen hotzikara ez zen hotzagatik izan. Erraldoi indartsuaren ahotsa tenore ahots lodia eta ederra zen. Begiratu ere egin gabe, eta oraindik ere barran makurtuta, istorio bat abesten hasi zen. Patuak betirako goi mendi lanbrotsuetako haitz gogorretan bizitzera eramandako artzain gaztearena zen istorioa (…) bere zoriontasun une bakanak gau oskarbietan izaten zirela aipatu zuen; orduan, bailarara begiratzen zuen eta nekazari baten etxean argi goxoa zegoela ikusten zuen eta argi horrek familiako zoriontasuna eta erosotasuna adierazten zituela ikus zezakeen”.

Azoka eguna denez, taberna lepo dago, eta miresmenez animatzen dute artzaina: “Amaitu zuenean nekazariarentzat animo oihuak egon ziren eta artzain bizitzari burla egin zioten. Nire lehengusuak bere bi eskuak igurtzi zituen. ‘Oso ona izan da. Gaur gauean sasoi betean dago’”.

Artzaina ere saloon bateko pistola duelurako posturan jarriko da, literalki: “(…) zutik jarri zen modu hunkigarri batean herritarren aurpegietara begira, esku batekin barra heltzen eta bestea bere gerrian jarrita; modu honetan kapa atzerantz erortzen zitzaion”. Eta kontraerasoari ekingo dio:

“Une batean bazirudien artzainak nekazariaren istorioaren ildo berdinari jarraitzen ziola. Bere abestiaren hasieran artzain gaztea mendigaineko haitz gogorrean aurkitzen zen, ilunpetan eta triste. Gero, bat-batean artzainak bailarara jaistea erabakitzen zuen eta argiturik zegoen nekazariaren etxeko leihotik begiratu, faltan botatzen zuen zoriontasuna ikusi ahal izateko. Berak espero zuen eszena zoriontsuaren ordez, sukalde narras bat ikusi zuen, ordea, umeak borrokan eta, azkeneko desengainua, emaztea nekazariari erratzarekin joka, azokaren ondoren bere lagunekin beranduegi arte edaten gelditu izanagatik”.

Narratzailearen lehengusua nekazariaren aldekoa da, harroputzegi ikusten du artzaina:

“’Nik uste artzaina zure gizona bezain ondo aritu dela’, esan nion nire lehengusuari ahapeka.

‘Ez da nire gizona’ esan zidan lehengusuak, haserre. ‘Beti saiatu izan naiz horrelako kontuetan inpartziala izaten. Halere, nire gusturako artzainak bere burua serioegi hartzen du. Nik uste bere burua beste Etxahun bat bezala irudikatzen duela’”.

Eta lehiak Etxahun eta Otxaldek oso aspaldi batean izandakoa dakarkio gogora:

“’Izen hori gogoan dut’, esan nion. ‘Behin Amerikan nire aitak Etxahun eta beste gizon baten arteko lehiako bertsoak abestu zituen’.

‘Otxalde’, esan zuen nire lehengusuak. ‘Gaurko topaketak bezalakoak izaten ziren. Bere garaiko onenak ziren. Etxahun menditarra zen eta Otxalde berriz bailara bateko nekazaria. Taberna batean egin zuten topo oso zaharrak zirela. Abestu zutena oso ona izan zen, gogoratzen den inoizko saiorik onena’”.

Etxahunen istorioa kontatzen dio lehengusuak, emaztearen maitaleari beharrean, ilunpeak, nahastuta, lagun on bati tiro egin zionekoa. Oso western bateko istorioa baita. Bitartean, saioak aurrera darrai eta xehetasun guztiak jasotzen ditu testuak: bertsolarien aurpegiko keinuak, bertsoen bidez harilkatzen den istorioa, publikoaren animoak, isilune tarteetako tentsioa…

“Kantu hasiera eta iseka oihu txikiak barreiatu ziren tabernan, pianoaren teklatuko beheranzko nota irregularrak balira bezala (…) Barreak ez ziren oraindik isildu artzainaren erantzuna abiatu zenean. Baritono aberats batekin abestu zuen, eta nekazaria ez bezala herritarrei begira egin zuen (…) Artzaiak bukatu zuenean, eta bere jarraitzaileek euren onespena ozen adierazi ondoren, isiltasunak hartu zuen taberna. Erabat ezustekoa suertatu zitzaidan hainbeste soinu eta zalapartaren ondoren. Antzezlan batean baleude bezala, beltzez jantzitako herritarrak euren edarietara itzuli ziren, isiltasunean pentsakor, edo saioko bertsoak errepasatuz euren artean xuxurlaka hitz eginez (…)”.

Bukaerak ere tonu horri eusten dio, baina, adornurako gaitasuna gorabehera, egileak bertsolaritzaren esentzia ongi ulertzen duela ere argi gelditzen da. “Nor izan da irabazlea?”, galdetzen dio narratzaileak lehengusuari. “Horrek ez du asko axola”, esan zuen: “Abestu dutena garrantzitsua eta behar beste ona izan bada, gogoratua izango da eta berriz abestua”. “Abestu dutena ez bada garrantzitsua izan”, gaineratu zuen sorbaldak igota, “gutxienez gau euritsu baterako entretenimendua izan da”.

The Basque Troubadour, Robert Laxalt, The Atlantic Mountly, 1963ko urrian.

My cousin and I had come down to the village after a day in the high, wild passes of the Pyrenees. It was nightfall, ande there was a drizzling rain. We were wet and colk, and we stopped at a little tavern for a warming drink.

There had been a market that day, and the tavern was crowded with those paysans who has stayed late and were now faced with the prospect of outwaiting the rain. And as on market days, they were in noisy good humor. We found a place at the en of the bar, next to a mountain of a man with a ruddy face and a beret tipped back on his head. He and his comrade were trading stories and every once in a while a rich laugh would come burbling up from jowly depths.

My cousin and I sipped a steaming mixture of coffee and brandy. Bertsolari my cousin said in a low voice.

The word rang a bell somewhere in my uncertain Basque vocabulary. Troubadour my cousin explained, inclining his gead toward the man´s broad back. ‘He is a troubadour’.

‘Will he sing’ I asked.

My cousin shrugged. ‘Perhaps. But I don’t think so’.

The door to the tavern opened and a figure came in out of the darkness, shaking the water form his umbrella. He wore the unmistakable garb of the shepherd, a wide beret, leggings wrapped tightly around his lower legs, and a long blue cape for a raincoat. His face was of the ancient Basque type, long and razor-lean, and there was a pride almost to arrogance in his bearing. He waved in answer to the greetings and his black eyes flicked over the bar. When his gaze came to the huge paysan standing beside us, it stopped. He nodded with dignity, hooked the handle of his umbrella into the collar of his cape, and walked to the other end of the bar.

‘Ah,’ my cousin said, biting hi slip in satisfaction. ‘There will be singing, all right-‘

The noise in the bar resumed, but now there was an undercurrent of glee and expetation running through the laugher. Somewhere down the bar, someone sang a snatch of song, and another joined in. There were hoots of disaproval, because it was badly sung. I learned later that it was sopposed to be.

‘We are in song” My cousin whispered. ‘Soon, it will begin.’

I looked at the paysan standing next to us. He was hunched over the bar, but in an easy attitude of waiting. His eyes were crinkled in flesh, and there was a mischievous smile on his lips. The transition from roug music to the business at hand was a subtle one. The little bursts of song and the cries of derision moved down the bar, like erratic descending notes on a keyboard.

The chill that coursed my back was not from the cold. Out of this burly giant came a tenor voice that was beautiful. Without looking up, an still hunched over the bar he began to sing a storu of a young shepherd fated to live forever in the cruel crags an swirling night mists of the high mountains (…) he coyld look down into the valley and see the warm light that peeped from the window of the house of a paysan, and contemplate all the familial joy and comfort that the light meant”.

When he finished, there was a roar of bravos for the paysan and mockery for the life of a shepherd. My cousin rubbed his hands together. ‘That was delicious. He is in good form tonight’.

The laughter had not even died down when the shepherd´s response stilled the rest of it. He sang in a rich baritone, an unlike the paysan he stood dramatically facing the villagers, with one hand holding the bar and the other cocked on his hip, so that his cape flared out behind him.

For a moment it seemed that the shepherd was but adding to the paysan´s story. His song began with the young shepherd on his high rock, sorrowfully regarding the faraway light in the darkness. Then, with sudden resolve, the young shepherd decided to descend to the valley and peek through the window so that he could see the joys he was missing. Instead of the blissful scene he had expected, he saw an untidy kitchen, brawling children, and the final disappointment- the paysan´s wife beating him over the head with a broom for drinking too late with his comrades after market.

The shepherd was nearly finished with his response before it came to me that he had not only turned the paysan´s own story against him, but had done so without changing the melody or the rhyme.

Suddenly, as the shepherd finished his response and his champions had shouted out their approval, a silence fell over the tavern. It was complete an unexpected on the heels of so much sound and noise. As if in a play, the black-garbed villagers turned to their drinks, struck silent attitudes of thought, or spoke to each other in low tones, savouring verses from the exchange.

’I think the shepherd has got your man on the run’. I whispered to my cousin.

‘He is not my man’, said my cousin offended. ‘I make it a practice to be impartial in these affairs. However, the shepherd takes himself too seriously for my taste. I think he fancies himself to be another Etchahoun.’

’I remember that name’, I said. ‘Once in America my faher sang the verses of a contest between Etchahoun and another man’.

‘Ochalde’, my cousin said. ‘It was such a meetings as this. They were the best of their time. Etchahoun was from the mountains, and Ochalde from the valley land. They met in a tavern when they were very old. What they sang was good and it was remembered. But for my taste, the best of Etchahoun´s verses came from the tragedy in his youth. Do you know the story? (…)

‘Which is the winner’ I asked my cousin. ’That matters little’, he said. ‘If what they sang was important and beautiful enough, it will be remembered and sung again. If what they sang was unimportant’ he shrugged, ‘it was at least a diversion for a rainy night’.

[1] Ik. RÍO, D. (2002): Robert Laxalt: La voz de los vascos en la literatura norteamericana. Bilbo: Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatearen Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia.